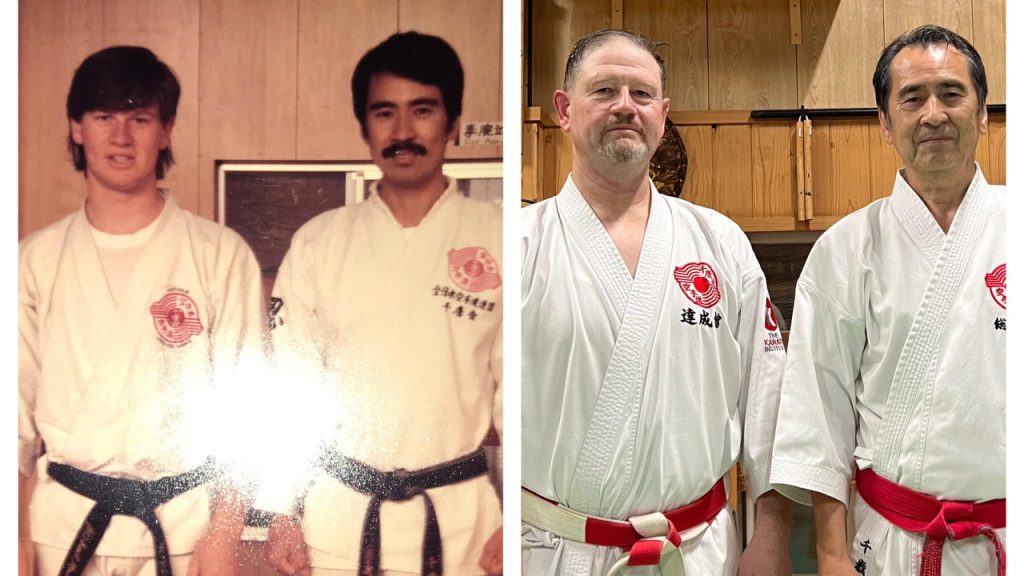

Part 2 of an interview we did with Noonan Sensei some time ago. Noonan Sensei is currently the most senior ranked teacher of Chito-Ryu Karate-Do in Australia. In this episode he share his experiences visiting Japan for the first time as a young man.

—- Transcript —-

Sandra: Hi there again. Today it’s time to continue on with part two of the five-part interview with Noonan Sensei.

Martin: And if you haven’t already heard the first part, be sure to go back and listen to the previous episode.

Sandra: Yeah, do that. It’s great. And in this episode, Noonan Sensei will be sharing what it was like going to Japan to train for the very first time as a young man.

Martin: We’ve noticed everybody faces challenges in life, some big and some small, but not everyone has a way to navigate these problems.

Sandra: It’s not always easy, but we found that we always keep coming back to what we’ve learned from our years in the dojo.

Martin: And that’s what this podcast is all about.

Sandra: Helping us all find the solutions to life’s problems, or even better yet, to remove the problems before they arise.

Martin: This is Martin and Sandra Phillips, and welcome to the Karate4Life Podcast.

Sandra: So I guess for you, I’m sure there were some really tough days in the dojo growing up, going from white belt to black belt. So has there been any times when you wanted to quit karate? So you’ve been training for a number of years?

Noonan Sensei: Yeah, yeah. Not that I quit. One, I mean, I still remember it to this day.

Steve Davison had hands like mallets, like little steel mallets. They were, it was like they were heavy. So he’d make a fist and his fist looked like a mallet.

And I remember one day we were training and he did something and he hit me in the kidneys twice. Very fast, very sharp. There was no malice in it or anything like that, but it was just so, I don’t know whether it was the pain of it or if it just had an emotional effect on my body.

Because I know now, which I didn’t know then, that sometimes if your organs experience some type of like penetrative hit, you know, and they get shaken up, sometimes they can cause an emotional reaction. I’ve seen that happen to people. But, so I don’t know what it was, but tears just came to my eyes.

And I’ve never, I don’t think I’ve ever tried in the dojo. I don’t think so anyway. But that day, I don’t know how old I would have been, maybe 16, 17 or something like that.

I couldn’t, I just couldn’t stop. And it was, you know, it was very embarrassing because you can do that. And get on with it.

So, but I never felt like quitting at all. Yeah, yeah. Sometimes you stay, I feel like quitting, but you don’t really feel like quitting.

I think we all experienced that. We all know what that feels like. When I first went to Japan, you know, I had a big head and I felt I was a big shot.

And I trained really hard here. And I did lots and lots, lots and lots, but I did all the tournaments that we used to do, that we could do, because there wasn’t a lot of them. And I’d be the only guy in the dojo to enter.

I’d just go by myself, because nobody else would be there. And ultimately, Steve Davis and Steve Sensei would turn up and just be there as a support for me. Or a couple of my buddies in the dojo would turn up, but they wouldn’t fight.

You see, they wouldn’t enter. They’d just turn up to, I don’t know, be my fan club or something. But anyway, so I felt pretty good about myself.

And I went to Japan, and then it might have been the first morning training or whatever it was, it was very early on that I just realised that I’m way, way, way, way, way off the mark here. And no disrespect to my teachers whatsoever, as I’ve just explained to you, but technically, it was a different world. And I felt I just didn’t understand any of this.

And that was very, that was heartbreaking. I wouldn’t say I was back in my room crying or anything, but I was pretty depressed about it. In that little, I was sleeping in the tatami room, which both of you know downstairs at the time.

And that was pretty hard. That was kind of heartbreaking, I suppose. And I went to Soka, and I said to Soka, I want to start at white belt again.

That’s what I told him. I said, I don’t want black belt. I want to start again from the top.

And in his wisdom, he was very young then, he was only 35. But he’s still still wise. And he said, No, no, you’re good.

I don’t know what he meant by that. But it was encouraging enough to say no, don’t do that. Just just start training the way I tell you from now on.

And so I would say that that’s probably the closest I’ve come from a karate sense. Sometimes you have personal things in your life, which make karate hard to do. Because there are things that you need to take care of or possibly philosophical challenges you have with the things that you do.

And having done karate from 13 years old, that sounds old now, doesn’t it? That sounds starting like I was old when I started because we get kids that start at four. I don’t know if you have younger younger ones than that or is it for your force?

Okay, so for I don’t think you can do anything with kids under four, to be honest with you. Certainly, I don’t want them in this dojo running around. But from four years old, you can kind of kind of control them.

But so but 13 if you if you think of a young man, you know, 13 years old, and you kind of become shaped by the things around you. And if you’re in karate all the time, living and breathing it, then that kind of shapes you. So I suppose at some stage in your life, you look back and you think, you know, you know, am I going to keep doing this?

Or is it good for me? Whatever. So everybody has those challenges.

And I have certainly experienced those. But from a karate perspective? Yeah, maybe I don’t think I’ve ever thought I wanted to quit.

But Japan was probably the first visit was the closest thing. For maybe a split second, I doubted why while I was doing this, but it didn’t last, it wouldn’t have lasted even more than a split second. And I had decided I had my solution.

And that was to go and start again. I’ll just start again. That’s what I thought.

And that’s so yes, in terms of giving up. It’s a long winded answer.

Sandra: But that’s it’s fantastic. I think it’s, it’s great that people learn. I mean, people who just meet you now, they’ll see you as 7th dan Kyoshi.

And they won’t appreciate that journey that you’ve gone through to get to that point. So I think that’s a great answer. So thank you.

Okay, so you started to share a little bit about Chito-Ryu Karate in terms of how it’s changed. I guess, I dare say, and if I’m wrong, please correct me. You’re one of those pioneers who have helped change the direction of Chito-Ryu in Australia.

Noonan Sensei: Yes, I have.

Sandra: Could you share if you felt if there’s a way to share, you know, how back when you first started, how much it has changed and in your thoughts?

Noonan Sensei: Well, it’s developed. It’s developed. And the important thing that this point is to say, to reassure the people that went before us that they did a great job, or else we wouldn’t be here.

That’s, that’s very important. So change, maybe change is a bad word. I don’t think it’s changed at all.

It’s developed. It’s evolved. I think, I honestly think we’re probably still, we still go in the same direction.

I know that Bill Kerr couldn’t have started his dojo for any other reason but to propagate karate. I think he used to charge us 50 cents a lesson, if you paid. Some people didn’t pay, I don’t think.

And it was increased to a dollar at one stage. Something like that. So I’m quite sure that Kerr sensei, that Bill sensei wasn’t doing it for any other reason that he loved what he did and he wanted to share it with others.

And so that’s really important to say that. Now having said that, of course, the more contact you have with the source, things will change and the more time you have to spend on it. So I’ve, I left, I finished my HSC on, in 1985.

I think it was November, yeah it was November 1985. It was my last exam and the next day I had a flight booked. So I finished my HSC and the next day I was on a plane.

And it wasn’t, as I said before, it wasn’t easy. You had to get planes and buses and another plane and a train and this and that. And nobody spoke any English and there were hardly any signs, well there were virtually no signs in English.

And my Japanese was non-existent apart from a book that Steve had given me. And so I got there and because I was then 85 and 86 and 87 and 88 and 89 and 91 and every year, at least once a year. And I had really encouraged and pushed and begged and groveled and said to Soke, you have to come to Australia.

And we used to call him those days, we didn’t call him Soke, we used to call him Chitose Sensei. And I really asked and pushed and please. And I think it was in 86 or 87, was it 87?

87, that was his first visit. And so of course with all, with more information, with people studying the information, with more people going, more access, the karate improves or it gets closer to what it should be, it gets closer to the source. And that’s what happened with the karate here, that’s how it changed.

I mean, it’s changed technically, it’s dramatically changed technically, dramatically. But I think the spirit, I think the spirit, the spirit that they had back then has not changed. In fact, it might have even been stronger than it is now.

I don’t know, I couldn’t say that. So I think it’s best put like that, yeah, rather than go into any details of what’s, you know, what’s changed. Of course, our understanding of the things like Tanden and Shimei and Kime, you know, we could go on.

That’s a day’s talking in it, you know, of itself or longer. But those are the things that we started to understand. And we only understood the very, in a very small way to start with, you know, just a little, little, it was a drip.

And then, but as you keep training, as the information keeps getting more and more, and you keep improving, you keep searching for more answers. And you grow and the people around you who are training with you or like your colleagues around you, they get better. And you see them getting better.

And that forces you to get better. And I’m very strong believer in that iron sharpens iron. So the better the people you have around you, the better you’re going to be, you know, you’ll run fast if you run with fast runners.

So I think that’s basically it’s fantastic.

Sandra: Okay, so we’re touching on your experience with Soke Sensei now, as you keep on going down that path. I know earlier in this interview, you were discussing that you’ve got a story to tell in your first time going to Japan. Let’s maybe go on to your first time going to Japan, what you experienced in terms of your travel?

Noonan Sensei: Oh, yeah.

Sandra: Well, let’s see if we can.

Noonan Sensei: Okay, well, as I said, it was, it was difficult to get there. So you had to get a flight to Tokyo, Narita, then you had to get a bus to Haneda, and then you had to get a flight to Fukuoka, then you had to get a bus to somewhere else, and then a train into Kumamoto. And then we were in Kumamoto station, and I was supposed to get a tram or something, but I was, you know, this is 24 hours of travel now, or more.

And I opted to try and get a taxi. And you would know that when Soke sends your certificates, your Dan Ranks, they come in a cylinder, and it’s got the address of the dojo on it. So I had that.

I had that. And so that’s all I had. Because all that had happened was, it was letter writing those days, not faxes.

So Bill Sensei had written a letter, I’m sending a student, Michael Noonan, he’ll be there in November. There was no date, and the reply came back, that’s fine, or something, you know, send him, go for it. So, of course, growing up in Australia, you expected taxi drivers to know where they were going, or have a street directory those days, there were no Google Maps.

But I didn’t realise that in Japan, and again, I could be a little bit out here, but from my knowledge that when areas were established, if you were the first house, you were number one in that area. If you’re the second house, you’re number two, but number two could be over there, and number one could be over there. Now, they have changed the system recently.

So I couldn’t understand why this taxi driver, I’m trying to, this is where I want to go, and he’s got no, he gets all the other taxi drivers together. Now, of course, my first trip to Japan, if you saw somebody else that wasn’t Japanese, if you saw another white guy or something like that across the road, you’d both cross the road to meet each other just to say, oh, what are you doing here? It was like that, and people would come up to you and try and test their English on you.

I remember being on a ferry to go to Shikoku to meet Taneda Sensei’s family, which was another story in itself that shall not be told ever on video, and if Taneda Sensei sees this, he’ll know why I’ve said that. But I remember on board this big ferry, seagoing ferry, a Japanese guy came up and was practicing English, and he wanted to know, did we, have I ever eaten a koala bear? That’s a true story.

He wanted to know what it tasted like, and I had to explain to him that we don’t eat koalas, but so it was a bit like that, you know, nobody, you know, people were friendly, and they wanted to help, and very, very honest, you could leave your wallet on the street, and you could pick it up the next day, or somehow someone would have found where you are, and your wallet would come to you. It was like that, so, but I couldn’t work out these taxi drivers, there’s a big group of them now, and then more come, and then they get on their two-way radio, and I can hear them, and finally somehow someone works out, I think they called the dojo or something, and of course it was near Chuo Pool, which back in the day, everyone has been there, back in the day, that’s what you tell the taxi driver, so they get you close, and then you can give them directions from there. So I arrived, and I knocked on the door, and a gentleman opened the door that I thought was Soke, a Chitose sensei, and I bowed deeply, and then he said something with a Canadian accent, it was Taneda sensei, I don’t know if he remembers that, but anyway, Soke was out at the time, but he came back, and the first thing he did was give me, just gave me a new gi, and his mother was there, and she looked after me, and made sure I had enough blankets, and told me what I had to do, and then, so training was quite hard in the morning, five more, six mornings a week, five mornings at about six or six thirty a.m., and then I can’t remember if it was eight or ten o’clock training started on the Saturday, but the Saturday training was for two hours, I’m not sure if Martin, if you had the same thing, was it? Yeah, six days a week, it was tough, and then you had the evening classes as well, and there were quite a few of those those days, so, but, and it was difficult because my body wasn’t used to that kind of training, it was rather difficult for me to get used to it, and then the other challenge was food, because I grew up in a quite a little cosmopolitan environment, in the sense that a lot of Mediterranean food, and things like that, because my friends were from, you know, different parts of Europe, or the Mediterranean, and because I’d be over at their house, and their mothers would feed me up, and shove food down my, which I loved, but I never really had any Japanese food, we didn’t even have Japanese restaurants here, we had, we had, I think we had one, maybe, if it had been open at that time, it was a Suntory restaurant in Kent Street, if anyone old would know that one, but I didn’t like fish, I didn’t like seafood, I didn’t like raw stuff, it was like stomach turning to me, I couldn’t believe, and we used to eat three meals a day with Soka-sensei, so first morning, because what’s for breakfast, miso soup, rice, what looked like a boiled egg, what looked like a boiled egg sitting there, and of course fish for breakfast, and I thought, oh okay, the miso soup’s okay, that’s good, whatever was put in front of me, I politely ate, barely, I could just barely, I’d squeeze it down, trying to get it down, and wash it down with some ocha, some green tea, so then I thought, okay, what am I going to do with this egg, the eggs are all right, I don’t mind a boiled egg, that’s easy, but before I had time to do that, Soka said, this is how you do it, or words to that effect, and he made a little hole in the rice, and then of course he cracked the egg, which was raw, not boiled, into his rice, and then he put shoyu, and then he mixed it all up, okay, great, now I just had fish, now I’ve got a raw egg, so it was tough, and then the good people that they were, because it was not common to have foreigners there, so people would, a lot of people would come and visit and take you out for dinner, and they’re really trying to put it on for you, and make a real, you know, be very generous, and you know, but they take you to a sushi restaurant, man, wrong restaurant, and I’d have to, you know, politely eat what was in front of me, and it was honestly, it was almost like torture for a while, and someone finally came along and said, you don’t look well, I’m going to take you, what do you like to eat, and I said beef, meat, and so I’ll take you to a steak restaurant, okay, now my mother prepared steak, and she cooked it until it was cardboard, like it, there was no rareness or juice left in it, it had to be well, well, well done, that’s what I was, food I was used to, and of course the steak comes out, and I cut it, and it’s bleeding everywhere, now now, and I politely asked for it to be cooked better, and I had to send it back twice, and it was still rare, because they didn’t want to ruin the steak, look, suffice to say, that I got over all that, and I am, you know, the biggest fan of Japanese food, I don’t think there’s many people that love Japanese food as much as me, I love sushi, I love all the kind of weird sushi stuff that’s out there, I love rare beef, and everything else, so that’s one thing that karate influenced my life, that I would have never ever expected when I started, I didn’t expect it would change my palate, change what I like to eat, so, but it was a challenge, because you’re eating food you’re not used to, you’re training where you’re not used to, you’re in a different environment, so it took a bit of getting used to, and I got, you know, eventually you get used to it, eventually you get used to it, and you’re feeling, you’re starting to enjoy it, and so it started my, when I got there, it started like, this is really hard, and I don’t know if I can, I don’t know if I’m going to get through this, you know, the doubts creep in, but by the end of it, you don’t want to leave, you know, and I took a group of students there in 2012, for the first time that I’d taken students, and they were only very, they hadn’t been in karate for very long, maybe two years, or three years, one, two, three years maximum, maximum, and the first day at training, I looked at all their faces, and I could see that they all, and I had warned them, I’d warned every single student, do you know how hard this is, this is hard, this is not for the faint-hearted, don’t go over there and embarrass me, I’m just warning you, if you want to come, you’re going to do, you’re going to get through this, so they knew, and they’re like, yes, no, no, no problems, we’ll, that’s fine, we’ll do it, yes, male and female alike, and of course, after the first training session, I could, I looked into their faces, and it was extremely hot, we’d gone in like June, July, or something like, killer, and I just looked into their face, and I could see everyone saying to themselves, why did I come to this, what on earth made me think that I should do this, but guess what, at the end of the trip, no one wanted to go home, and so if you’re, if you are out there planning to go to Sohonbu, I would, I would do it, I wouldn’t think twice, just go book a ticket, just go and do it, if you think about it too much, you’ll find a reason why you shouldn’t go, there’s always a reason why not to do something, and if you think hard enough, you’ll come up with the best reason ever not to do it, but I would throw caution to the wind, and book a ticket as soon as possible, and get over there, of course, with the permission of your teacher, and or talk to your teachers, and your sensei, talk to your sensei, and make sure that they feel it’s the best thing for you as well, but if, if you’re serious about your Chito-Ryu, I’d get across there as soon as possible.

Martin: Thanks for listening to today’s episode on the Karate4Life podcast.

Sandra: If you found this episode useful, please comment on our website karate4life.com.

Martin: Share it with your friend via social media, and don’t forget to tag us, hashtag karate4lifepodcast, and if you’ve got a topic that you’d like us to cover in future episodes, or a question you’d like to ask about karate or life, please send us a message, we’d be more than happy to share our thoughts. Thanks again for joining us, and stay tuned for the next episode, where Noonan Sensei shares a bit more about his personal karate history, and here’s a few brief highlights of what’s to come.

Sandra: All the feedback I got from Soke Sensei was, you’re just too tight, you’re too tight, you’re too tight.

Noonan Sensei: I think Soke must say that to every single student. He used to stand there and laugh, my karate was that bad, I think, you know, he just used to laugh at me, too tight, always, that’d be like every lesson, and he would, he, you know, he exaggerates things to show you what he’s talking about, right? I got everything, my head was down, my this was this, my that was that, my shoulders were up, my blah, blah, blah, I mean, I had everything wrong with me, and, and, you know, and then you think you’ve got it right, and then it’s too tight.

If you apply yourself hard enough to anything, you’ll overcome, and I suppose that’s what karate really teaches you, and I can see the same discipline in things like classical music, I’m sure dance has very similar disciplines, and so I don’t say it’s just karate, but karate is a great avenue for it.